Göbekli Tepe and Trade

Pathways of Migration and Cultural Integration

The origins of the Akkadian people and their ascendancy in Mesopotamia can be understood as a process of migration, trade, and cultural integration rather than sudden conquest. By the mid-7th millennium BCE, southern Mesopotamia’s fertile wetlands and marshes supported thriving Ubaid settlements, whose inhabitants were intimately adapted to complex riverine and marsh environments. Among their most critical technological adaptations was the development of small watercraft suitable for navigating the Tigris and Euphrates waterways. Archaeological evidence—bundled reeds, reed mats, and depictions on cylinder seals and later Sumerian art—demonstrates that these boats were in practical use. Early cuneiform records from the late 4th millennium BCE further confirm that river transport was a standard component of economic and social life, indicating that these communities were already building and using boats capable of carrying small loads or several individuals. These vessels facilitated trade, seasonal mobility, and fishing, providing the logistical backbone for early exchange networks across southern Mesopotamia.

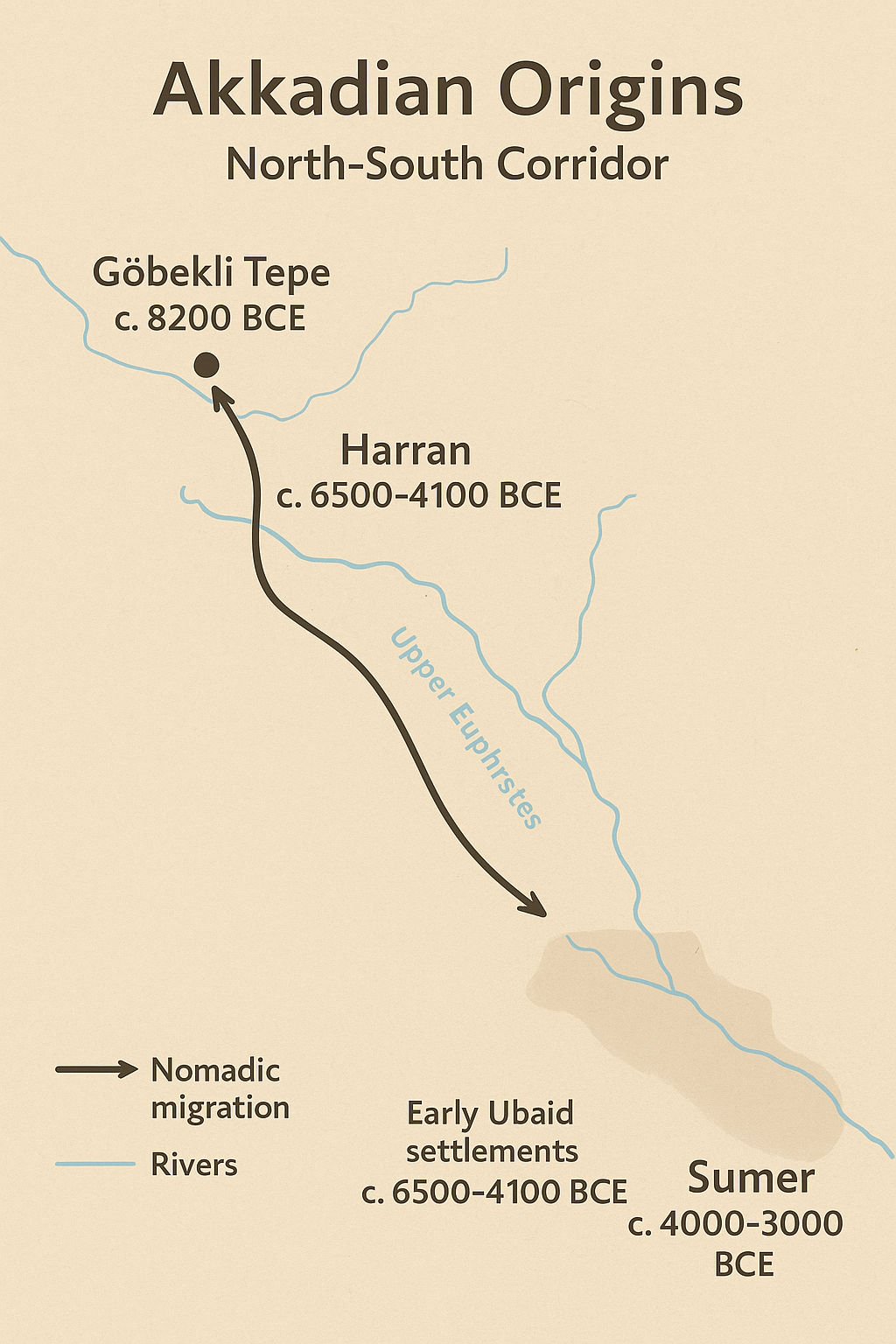

To the north, Semitic-speaking nomadic and semi-nomadic groups inhabited the highlands and plateaus of Upper Mesopotamia and southern Anatolia, traveling seasonally along the corridors of the Tigris and Euphrates. While these groups were not the builders of Göbekli Tepe, their trade networks extended as far as the site’s plateau, allowing for the exchange of goods and ideas over millennia. Environmental pressures, including increasing aridity and the gradual desertification of parts of Anatolia, encouraged these nomads to move southward toward the fertile lowlands. By the time of the earliest Ubaid settlements (c. 6500–4100 BCE), these northern groups were well-positioned to integrate into the emerging urban societies of southern Mesopotamia.

Harran (Biblical Haran) illustrates the strategic significance of this northern hub. Situated on the Upper Euphrates corridor near Göbekli Tepe, Harran provided a waypoint for north-south migration, trade, and cultural exchange. According to the Biblical narrative, Abraham, his father Terah, and his nephew Lot lived in Haran before moving to Canaan, reflecting the real-world function of this corridor as a conduit connecting northern and southern Mesopotamia. While Abraham himself was unlikely to have been Sumerian, he plausibly represents a northern Semitic-speaking nomadic lineage interacting with southern Mesopotamian urban centers, echoing the broader pattern of nomadic integration into Sumerian society.

In this context, Akkadian-speaking migrants adopted Sumerian administrative systems and the cuneiform script, initially developed for the Sumerian language, adapting it to their own Semitic tongue. This process of linguistic and cultural adoption allowed them to establish governance structures that drew on Sumerian precedents while articulating their own social, political, and religious identity. Rather than a single moment of conquest, Akkadian prominence emerged from gradual integration, technological and administrative borrowing, and strategic migration, facilitated by both geographic opportunity and environmental necessity. Göbekli Tepe’s geographic proximity to the Upper Euphrates corridor serves as a symbolic and practical reference point for these north-south interactions, highlighting the long-standing importance of this route in shaping the cultural landscape of early Mesopotamia. Through these processes, the Akkadians rose as a dominant cultural and political force, building upon—and eventually supplanting—the Sumerian city-state model.